It was a long winter. Despite the promise of snowdrops and celandine, rain fell almost continually. Fields were waterlogged . Ploughing oxen strained against their yokes but it was almost too much for a pair to drag the single-ploughshare through drenched clods of earth. Boys, whose job it was to lead the teams, came home crying with wet and cold and aching limbs. The men were little better. Their pain showed in their eyes, pausing at the hearth only to shuck their mud-encrusted trews, shovelling food into mouths too tired to chew or swallow, falling asleep where they sat.

Food was scarce. Soon the last of the grain would be gone and none dared breach the sacks destined for seed. Salt fish and meat clung to the bottom of the barrels stiff with brine. Though women foraged for fresh greens, there was little to find and small children began to wail with empty bellies.

“We must wake the God,” the old women grumbled. “He has slept too long this winter. We must go to him with drums and shakers and loud cries, forcing him to rise and strengthen the sun, so the fields will dry out and we can plant grain for the summer.”

It was agreed. On the day most auspicious for waking the God, when hours of darkness equalled the hours of light, the whole village met on the edge of the wood and began to dance. Their feet pounded on the bare earth. Men brought huge drums made from hollowed logs and covered in skins. They beat them with sticks, their deep booms resonating against the trees. Children shook rattles and shouted – glad to be free of winter houses where everyone told them to be quiet and still. They ran around chasing playmates. Older boys and girls ventured into the edges of the forest, whooping and shrieking, calling out to the God to join them in their games.

When they could leap and shout no more, the villagers gathered their drums and children, making ready to trudge back to the village and once more tend their flocks and cattle.

Gilda was troubled. It did not seem right to wake the Young God without waiting to see how he fared. She knew what young folk were like, with three lively children of her own including two year old, Tomaz, who should really be weaned, but there was little else to give him other than a thin gruel.

“You take him for me,” she said to her mother, lifting the child onto Ella’s back. “I’m going into the wood to forage. There may be some patches of greens I’ve missed. I’ll be home before dark.”

The old women regarded her daughter through narrowed eyes. Gilda’s words were simple enough and goodness knew they needed whatever she could find, but it was only half the story. It was not like Gilda to put anything or anyone else before her man and her children, but now was not the time to ask questions. Ella called the other two children to her and they began to pick their way carefully along the muddy track back to the village.

Gilda stood watching them until the path curled away down the hill out of sight. The sky was clear now. More rain had fallen during the night, but the pale blue canopy held only white clouds high above, moving fast in the freshening wind. Far away on the horizon, Gilda could see the sparkle of sunshine on a quiet sea. If no more storms came, the men could go fishing and everyone could eat.

Gilda sighed. It was not in her nature to deceive her mother. Petros, the children’s father was long gone, busy moving sows into their farrowing pens before they dropped their litters amongst the other pigs where newborn piglets could be killed before anyone could save them.

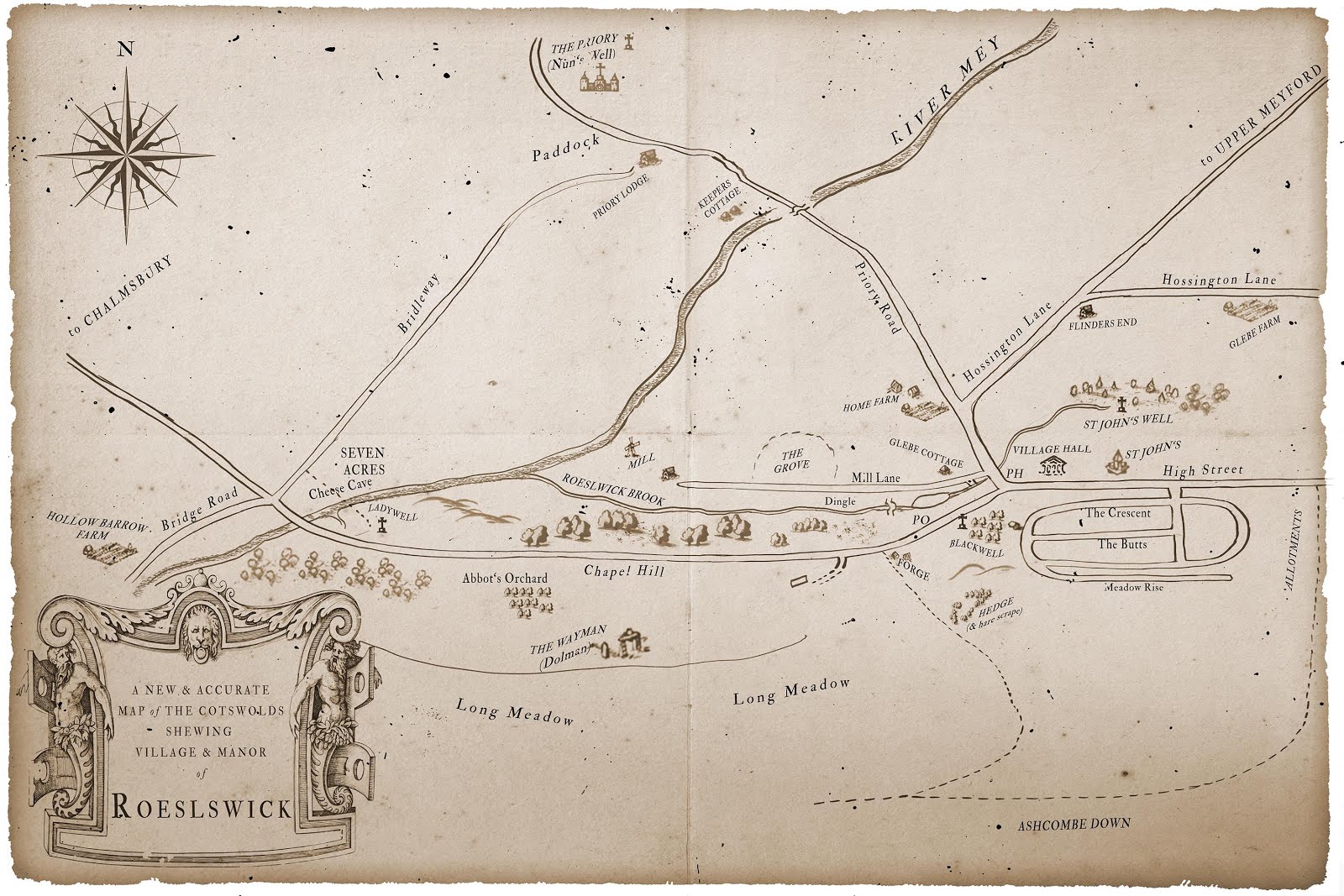

She turned towards the wood, taking the higher path deep into the heart of the forest where deer lived and wolves roamed. On the other side of the hills there were said to be huge caves where bears slept during the winter. Gilda’s grandmother used to tell stories of the day when a huge black bear with two cubs were seen fishing on the sea shore when her grandfather was a boy, but no-one had seen them since that time, so it may be hunters killed all there were or maybe they moved to another cave on another hillside, frightened by the noise of the fishermen and their dogs.

Gilda was not a good hunter. Though she could set traps for hare and wove fine nets for fishing, her eyes and arms did not move well enough together to allow her success in the hunt with bow and arrow or spear or even sling shot. She practiced with her peers as a child, but everyone else could hit the target when she still missed. In the end, her father said it was a waste of good arrows to make them for her and showed her how to weave gathering baskets from grasses and young hazel or willow shoots. When others went hunting, she stayed behind to mind children or took her baskets with the elders when they went gathering.

Gilda walked steadily upwards. Although huge trees grew all around her, it was still light within the forest. No green canopy grew to shut out the sun. Everywhere she looked branches were bare. Even when she pressed her head against their thick bark to listen for sap rising, she could hear nothing.

Until she came towards a less densely wooded glade. Here were carpets of bluebells and wild garlic. Primroses painted a yellow path of colour around the edges of the clearing, drawing her forward towards a low, sheltered rock covered in green moss. As she drew near, the moss shimmered in the sunshine and seemed to move. Long limbs stretched and a lithe figure sat up from the soft bed where he had been lying.

He sat, blinking in the sunlight as she approached. His dark brown hair was a wreath of curls around his head, but Gilda could see antler buds pushing their way above his crown. His skin was pale, as one who has been too long away from the sun and his legs were covered in fine brown hair, smooth as silk

He yawned and stretched again. “You woke me,” he said, fixing Gilda with deep brown eyes, like a fawn’s eyes, but older than the earth itself.

Gilda felt her insides churn. She was no shaman, used to travelling to the spirit world to talk with Gods and Spirits. Yet she knew he would need someone with him when he woke, to remind him of his duties, to guide him into a new world to do what must be done.

“We need you,” she said. “The winter has been long and wet. If you do not wake and grow strong, we cannot till the soil and plant our grain. There will be no grass for our cattle and sheep, no blossom on our trees, no plants to grow and feed my children and my man.

“If you do not mature, who will catch the maiden and sow your seed. The Mother will be barren, we shall starve and wither away.”

He blinked again. “What is that to me?”

“Without your strength, we cannot tend the earth the Mother provides for us. Without us, you are forgotten and the earth is bare, blowing away as dust upon the wind. No-one will manage your forests and the trees will die. The deer will over graze the young trees and the stags will kill each other in their fight to gather enough hinds around them in the rut.”

He shook his head, then slipped off the rock and stood on the ground, his feet pawing at the earth like a young stag. His head went back and his call echoed around the glade. It was not the deep roar of the mature stag, but rather the young male who stands on the cusp between childhood and maturity.

Gilda shivered. It seemed a lifetime ago since she stood on the edge of the forest at Beltane after dancing around the maypole with all the other young men and women. When the ribbons were all intertwined they climbed the path to the woods, laughing and giggling, wondering who would meet with the God amongst the trees. One by one the others fell behind, hiding in pairs behind bushes and brambles to play adult games with adolescent bodies.

Gilda found herself alone on the path until she heard the God calling. She did not remember going to him, nor what befell her that night. Petros found her wandering amongst the trees in the half-light of dawn, her dress torn and muddy. He took her back to the fire coaxing and soothing her until they leapt the flames together and the elders agreed their union.

They never spoke of that night again. The children she bore him were hale and hearty. If her eldest girl sometimes talked to unseen friends, they put it down to her age and knew she would grow out of it once her childhood passed.

Hearing the young God call brought back so many memories, but Gilda was no longer that maid, she was a woman, a mother. He needed someone to care for him and guide him.

He looked towards her. “I’m hungry.”

Gilda thought quickly. “The only food I have is my milk. It is yours if you wish it.”

He smiled at her, his brown eyes twinkling. Taking her hand, he led her around the stone where grass and moss together made a soft seat. He sat her down, lounging beside her as she loosened the lacings at her breast. Even though her youngest child was near weaning, his call had made her milk let down, dark wet patches, staining her blouse.

His fingers stroked her, drawing the material away from her breast. He traced the dark blue veins of milk down to her nipples, circling the aureoles, then catching the pale, blue/grey drops of milk on his fingertips. He raised it to his mouth, his long, pink tongue catching the drops and taking them inside his mouth.

He smiled again, nodding, as if to signify the taste pleased him. Then he draped himself across her, resting his head in the crux of her arm as he drew her nipple into his mouth and drank.

She felt the long, slow pulses of his tongue against the roof of his mouth and the streams of milk leaving her. She felt him swallow, each draught of milk filling his need and feeding his body. When that breast was dry, he turned himself, latching on to her with skilful ease. She stroked his head, rubbing the tiny antlers as they twisted through his hair, crooning the same lullabies she sang to her own children. She could not wonder how her milk should be so plentiful, only that he wished to feed and she could serve him.

When he was full, he lay in her arms and slept; the sun warming them both on the soft grass.

When he woke, he looked up at her, his dark eyes warm and loving.

“I will not forget,” he said. “Those who come to me without fear, without conditions, offering themselves alone, those I allow to serve me. This is your second time. Come to me again at Beltaine and I will quicken you. Your voice will mark my harvest and you will help the Mother bring me forth again at Yule.

“Go now. Follow the left hand path to the edge of the forest. Beside the rowan tree you will see a rock shaped like an eagle’s beak, under it flows a spring. Around the pool fed by the spring you will find ample greens for your children. Gather only what you need each day and it will keep both you and them until the grass grows again and other plants can feed you.” He kissed her cheek. When she moved to thank him, he was gone.

Gilda got to her feet and set off down the hillside, following the left hand track through the trees. When she reached the edge of the forest, she saw a single rowan tree standing beside a stone. As she drew closer, she could see the stone did indeed resemble an eagle’s beak, with clear water running from it. She was tired after her long walk, so she stopped and gathered the water into her hands and drank. It tasted cool and sweet.

The spring ran down into a tiny stream, which then flowed into a small pond. Just as the Young God said, around the edges of the pond grew thick, lush watercress, bright green and tasting hot in the late afternoon sunshine. Gilda filled her carrybasket, offering her thanks to Young God and the spirits of place who allowed her such bounty with which to feed her family.

“The Gods must favour you,” Petros said later, his mouth full of watercress. Gilda said nothing. Her milk was gone now. Tomaz was weaned, but he would not starve. Her thoughts turned towards Beltane and she smiled.

Saturday 20 March 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment